MedAdNews is a trade publication covering the business of pharmaceutical marketing. It’s like Advertising Age and Adweek, in that its editorial serves and celebrates an economic subsystem of advertising and communications agencies, except MedAdNews is focused on the services bought by pharmaceutical brand teams to create the content to position and promote prescription drugs directly to consumers and health care professionals.

It’s big business.

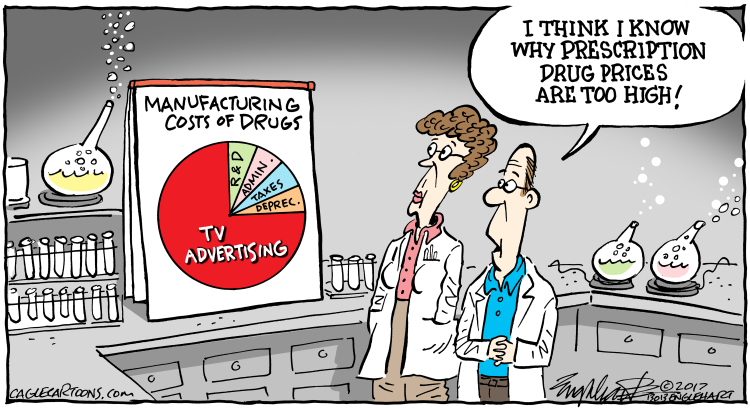

In 2016 alone, according to the Journal of the American Medical Association, the pharmaceutical industry as a whole invested somewhere around $30 billion on prescription drug advertising, promotion, public relations, disease awareness and sales campaigns across audiences, channels and therapeutic categories. The overwhelming majority swims in a sea of sameness, a monotonous repetition of banality flooding the zone whose signature is the “terminal smile” — the Standard Model looks like this:

Note: this is ad is not real.

It’s actually a parody campaign, a spoof, for a fictional medication to treat a fake psychological disorder.

It was created by Australian artist Justine Cooper as a social satire on drug promotion. Cooper intended the exhibit to be humorous. She recreated the entire drug marketing process, starting from the invention of a new disorder to the branding process of naming the drug, its pill and logo design, and promotional merchandise. The campaign was on display at the Daneyal Mahmood Art Gallery in New York City from February 8 to March 17, 2007 and included TV, print and billboard ads along with merchandise and branding material.

“It's just like any other advertising campaign and web site devoted to a drug, really -- the home page for Havidol features an attractive person smiling contentedly, a link to prescribing information, including a chemical formula, and the standard side effects spiel now familiar to anyone who's seen TV drug commercials,” wrote Melinda Wenner in her coverage of the exhibit for The Scientist (see “Designing a Disease -- and its Drug”). The site itself even contains TV and print ads, a self-assessment test to find out if Havidol is right for you, and customer testimonials. But look a bit closer. The drug is described as "the first and only treatment" for dysphoric social attention consumption deficit anxiety disorder, or DSACDAD -- termed "the #1 concern of contemporary life."

April is always special at MedAdNews.

It’s the month where drug advertising agencies publish their profiles in the magazine and submit their best “creative” in the hopes of winning a Manny Award. The Manny Awards, says the magazine’s publisher, “pay tribute to the creative work of agencies serving the healthcare market, their people, and their contributions to the industry.”

The prelude to this year’s edition, beneath the headline “Another Year of Changes, Growth” sets the stage with this odd retrospective from its editors:

“In 30 years of the Manny Awards, many things — technology, medicine, and ways agencies do business — have changed. But the healthcare ad industry continues to thrive and adapt to the new demands for relevance and creativity.

Think of where you were 30 years ago. Were you already working in healthcare advertising? Were you still in college or just graduated? Or were you in high school….?

Now think about what the media world was like 30 years ago. Network television was still king. The primary places to advertise were newspapers, magazines and radio, as well as direct mail.

And the internet was not really a thing.”

The gala ceremony announcing the many Manny winners (there were 40 categories, ranging from Best Managed Markets Campaign to Best Consumer Campaign - Radio/TV) was April 18. Which, as it turns out, coincided with the publication in JAMA of an editorial, “Lowering Cost and Increasing Access to Drugs Without Jeopardizing Innovation.”

The authors of the JAMA editorial are Robert M. Califf, MD, a former FDA Commissioner now at Duke University School of Medicine, and Andrew Slavitt, a former Acting Administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. They begin their view this way:

“US drug costs have reached unacceptable and unsustainable levels. Evidence shows that “financial toxicity” arising from drug costs and other medical expenses is reducing financial security for many families, and prompting difficult choices, as patients defer or forgo therapies they cannot afford.

In stark contrast, comparable countries negotiate drug prices and use drugs more effectively. Recent data suggest that other high-income countries have an average life expectancy approximately 3 to 5 years longer than that of the United States, which ranks last among high-income countries and is losing ground compared with peer nations. Although drug prices account for only part of these trends, they nevertheless add to disparities that dominate the trajectories of US health outcomes.”

They go on to give their perspective on the impact of drug promotion:

“Direct-to-consumer advertising, detailing, and excessive physician payments also drive up costs. A particularly troubling issue to health professionals is the increasingly brazen use of the internet, social media, and television for marketing based on marginal or unproven benefits under the protection of current legal interpretation of First Amendment rights.

Which brings us back to the central question of this post: should we continue paying tribute to the Standard Model of pharmaceutical marketing?

At a system level, the strategic effect of $30 billion a year on drug promotion in the United States, woven into the fabric of society over decades, has been to embed and sustain a feedback loop of deep mistrust, reputational fragility and pricing challenges with tangential impacts worldwide. See here for China, China Solidifies Drug-Buying Program That Saved $41 Billion; and here for Japan, Double-Digit Slashes to Hit 44 Major Drugs in 2022 Price Revision.

The feedback loop makes it hard for the industry’s “value” narrative to punch through and persuade, particularly against the opacity, complexity and information asymmetry of PBMs; it also feeds an ever bigger flywheel of dysfunction in a system of markets locked in stasis, managed by strategic atrophy, where ‘check-the-box’ roadmaps and PowerPoints cut-and-paste the same assemblage of words, doing little to spark creative leadership, the kind that can guide a $4 trillion health economy out of stagnation in imagination (for an excellent perspective, see Why Isn’t Innovation Helping Reduce Health Care Costs? in Health Affairs).

Another Market Forecast Meets a New Market Reality

A basic problem confronting structural change is vision to see new aspects of reality.

This includes surfacing deep assumptions and challenging the conventional view. Pharmaceutical companies are generally trying to solve problems of efficiency and optimization around better drug development and promotion. This is the wrong set of problems. The pharmaceutical industry, like many other industries and governments throughout the world, is flailing to find strategic fit because it has not adapted to the breakdown of Industrial Age ideas.

It's legacy thinking -- not technology -- that's maybe the biggest barrier to navigating the transition space to a new era. Leadership teams become kinetically-trapped in outmoded structures, orientations, incentives and schools of thought, doomed to be, always, in defense of whatever business model allowed them to be successful in the first place. The inertia of the Industrial Age mesmerizes us. And so the commercial withering continues.

Biogen is a case in point:

The approval of Aduhelm for Alzheimer’s had prompted the investment analysts at RBC to put 2026 sales expectations for the drug at $7.5 billion, while Leerink pencilled in $8.2 billion. But the ground truth is always different than policy projections and intelligence estimates and market forecasts. In its latest earnings report, Aduhelm brought in just $1 million in sales in the fourth quarter, compared to already diminished estimates of $2.8 million.

"When your back is against the wall, as a company, your base business is in decline, and investors don't believe in the pipeline that you have, M&A becomes much more important," Mizuho analyst Salim Syed said following the earnings call. "How transformative of a deal should we or could we expect in 2022? That's the question."

Tilt.

It’s too….linear….to point the finger of blame at any one character in the story of strategic collapse at Biogen. Reality is too complex to cleave so cleanly. Biogen is/was in the grips of its own feedback loop keeping the old disorder in place.

From the fiduciary responsibility of managing a publicly-traded company and the quarterly pressure to demonstrate growth and shareholder value, to the regulatory and policy context governing the rules of play in the pharmaceutical market, to an entire economic subsystem of vendors geared to launching and then sustaining what held the promise of becoming “one of the biggest launches in biopharma history,” the system itself could not see the structural change happening in its operating environment, nor reorient its thinking accordingly.

Common sense and the real-world were systemically forced-out of consideration by deeply-rooted analytical models; “optimized” solutions involved narrowly-framed decisions taken by specialists; isolated data feeds were pointing positive, but could not describe an overall failure in strategy; and management underestimated or misread the plate tectonics shaping the operating environment.

In other words, the paramount importance of Aduhelm sales, not only to Biogen but also for the galaxy of vendors feeding from its drug promotion budget, helped create the conditions for its failure.

The system destroyed itself.

Breaking the Standard Model

The new market reality that's emerging in the pharmaceutical industry is that the technical merits of a new drug are, more often than not, table stakes for business success. This is one reason why digital + drug discovery is an equation for the status quo, not commercial model innovation: the center-of-gravity for strategic thinking is still bounded in the context of the drug pipeline.

It’s time to get comfortable crossing the river while feeling for the stones.

“We don’t know if we’re going to succeed, but what we do know is what’s in place today isn’t working,” said Novartis president Marie-France Tschudin, in describing a novel approach the company is testing for the launch of its new cholesterol drug. To overcome the Red Ocean Problem in the market for new heart medicines, Novartis is pursuing an unconventional strategy, “one that turns the traditional drug launch on its head.”

Rather than big media buys in campaigns to win support from individual physicians (in Manny language, this promotion would fit in the categories of “Best Professional Campaign - Web” and “Best Professional Campaign - Print”) and demand from patients, Novartis is instead focusing on ‘value alignment’ with the business and technology agendas of the people who run large integrated delivery networks, an entirely different customer. The full story is here: Novartis Rethinks Sales Strategy for New Cholesterol Drug Launch

It’s the space in between “healthcare” and “life sciences” that is now ripe as source material for new storylines of value. This is one reason why Kenneth C. Frazier, Merck’s Executive Chairman and former CEO, joined General Catalyst last year. Frazier’s initial area of focus will be to help drive collaborative partnerships with healthcare companies and the pharma industry, a sector that General Catalyst believes is “under-leveraged” as an enabler of market innovation.

It’s a different thesis entirely.

The premise for strategy is based on the view that the pharmaceutical industry has kinetic potential to lead large-scale system change, rather than become a victim of it, and that that power is untapped at best, and misdirected at worst.

The conceptual impact from Biogen’s CMS slap down should be felt this way this: the Standard Model of pharmaceutical marketing is now operating outside the bounds of rationality. The “creative” in short supply is a new language from which to channel strategic imagination.

But then, who wins a Manny?

🤘

Originally published as a LinkedIn post on May 2, 2019; updated to integrate perspective on latest developments from Biogen, Novartis and General Catalyst

/ jgs

John G. Singer is Executive Director of Blue Spoon Consulting, a global leader in Strategy and Innovation at a System Level. Blue Spoon was the first to apply systems theory to solve complex market access and integration challenges in the pharmaceutical industry.