The Aduhelm saga provides broader lessons in systemic failure.

Biogen stock has plunged after reaching a six-year high in June last year, when Aduhelm was approved. The decline has wiped out more than $30 billion in Biogen’s market value, falling further after Biogen management disclosed in its earnings call last week that sales for Aduhelm were $1 million, missing the consensus estimate of $1.6 million, and issued weaker-than-expected financial forecasts for 2022.

Biogen also said that a $500 million cost-cutting program it announced in December would be expanded if the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services doesn’t not alter its decision that Medicare wouldn’t pay for Aduhelm except in the context of a clinical trial. Meanwhile, the “Biogen Departure Train Chugs On” — one week after Johanna Rossell, who served as Global Commercial Lead for Aduhelm, left for a leadership role at Enzyvant, two members of Biogen’s board said they are leaving.

This past week, Wedbush analyst Laura Chico wrote that it’s “time for a change” at Biogen. She laid out three options: Buy something, get bought, or “sell it for parts.”

In its brief life as a brand, Aduhelm has been led by strategy at a technical level.

The drug is/was part of a broader neuroscience product development vision at Biogen, involving more than 30 clinical programs. “These include our investigations into several possible additional treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, as well as other debilitating neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, ALS and stroke. We have spent more than $28 billion in research and development since 2003,” reads a statement the company issued at the time of approval.

(Not included in the $28 billion R&D are the fees and expenses for the army of vendors — an entire economic subsystem — Biogen used to create the drug promotion to consumers and health care professionals, the “disease awareness” campaigns, the media buy, and all the analytics behind the data. Also impossible to know is what Biogen is/was allocating for its information technology to support Aduhelm marketing and sales operations.)

When 2+2 = Oranges

A basic problem confronting structural change is vision to see new aspects of reality.

This includes surfacing deep assumptions and challenging the conventional view. Pharmaceutical companies are generally trying to solve problems of efficiency and replication around better drug development and promotion. This is the wrong set of problems. Biogen and the pharmaceutical industry, like many other industries and governments throughout the world, are flailing to find strategic fit because they have not adapted to the breakdown of Industrial Age ideas.

It's legacy thinking -- not technology -- that's maybe the biggest barrier to navigating the transition space to a new era. Leadership teams become kinetically-trapped in outmoded structures, orientations, incentives and schools of thought, doomed to be, always, in defense of whatever business model allowed them to be successful in the first place.

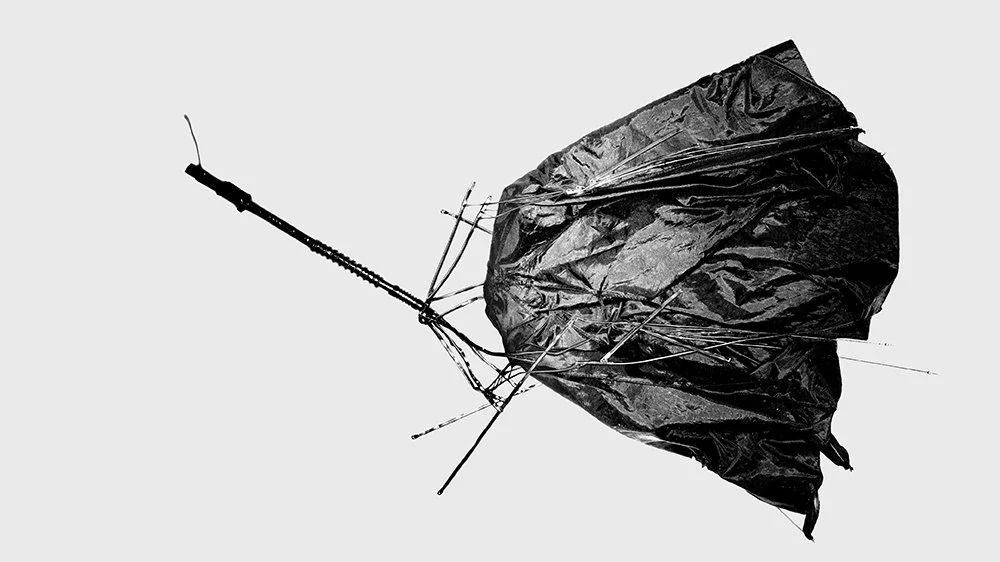

It’s too….linear….to point the finger of blame at any one character in the story of Aduhelm collapse. Reality is too complex to cleave so cleanly. Biogen is/was in the grips of a massive flywheel keeping the old disorder in place.

From the fiduciary responsibility of managing a publicly-traded company and the quarterly pressure to demonstrate growth and shareholder value, to the regulatory and policy context governing the rules of play in the pharmaceutical market, to an entire economic subsystem of vendors and advisors geared to launching and then sustaining what held the promise of becoming one of the biggest "one of the biggest launches in biopharma history,” the system itself could not see the structural change happening in its operating environment, nor reorient its thinking accordingly.

In other words, the paramount importance of Aduhelm sales, to Biogen and for the many industrial subsystems feeding from its drug promotion budget, helped create the conditions for the strategic collapse of Biogen:

Common sense and the real-world are/were systemically forced-out of consideration by deeply-rooted analytical models; “optimized” solutions involve/involved narrowly-framed decisions taken by specialists; isolated data feeds are/were pointing positive, but cannot/could not describe an overall failure in strategy; and management underestimates/underestimated or misreads/misread the plate tectonics.

The system destroyed itself.

It’s Hard to See The End of Things

Change comes in three wavelengths, says Kevin Kelly, a co-founder of Wired Magazine: There are changes to the game, changes in the rules of the game, and changes in how the rules are changed.

And so what's emerging as the building blocks for strategic success today is agility, a management team who can see, understand and rapidly adapt to what can fairly be described as a total change in context in the landscape for business.

Existential crises abound.

The world is now littered with dying companies, markets and industries buying into the myth of a simple recipe, the allure of new technology, and an obsession with tradition as they search for optimal solutions that don’t exist.

It’s the ‘leadership margin’ that now separates.

Said differently, opportunity comes from strategic leadership that can create the culture to collectively exploit structural change and find new identity in a world with hazy boundaries. To lead the next cycle of evolution in healthcare, we need to shift our creative and analytic focus to the system level, not the constituent parts.

"Healthcare" in the United States is a 'nested market', one massive and ever-expanding complex of interactions in a $4 trillion health economy that is wrongly understood, rewarded and regulated as isolated and independently operating spheres.

It’s time for management teams in industry + government to recognize, quickly, the foundational fragility of the Western mode of linear thinking – of breaking things apart to study them -- and understand that the weapons of mass entrenchment keeping the structural stalemate in healthcare alive are more conceptual than they are technical.

Seeing and thinking in terms of systems is the mother lode to mine for a new imagination, the kind of creative leadership that solves for strategic atrophy. This isn't a moral argument about "doing the right thing,” but an understanding that radical forces are changing not just the rules of the game, but the game itself.

Poor strategy is expensive.

The skill in short supply is not technical, but visionary, able to articulate and propagate a new direction, and manage the transition to market innovation. For the pharmaceutical industry, I would argue that the biggest learning from Aduhelm is this: there’s a difference between bringing a new drug to market and bringing a new outcome to market.

🤘

/ jgs

John G. Singer is Executive Director of Blue Spoon Consulting, a global leader in Strategy and Innovation at a System Level. Blue Spoon was the first to apply systems theory to solve complex market access and integration challenges in the pharmaceutical industry.