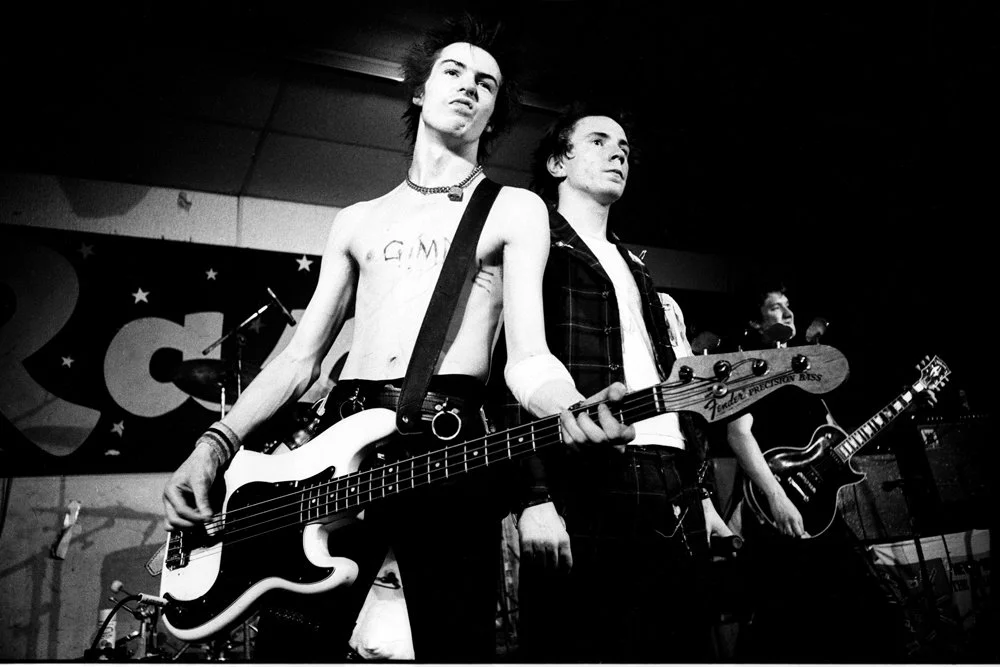

In 1977, the Sex Pistols released their first and only studio album.

Raw, rude and a rejection of everything rock 'n' roll, 'Never Mind the Bollocks' became the battle cry of UK Punk. With a legacy that loud, one album was enough.

Punk was hardcore Zen.

It was a completely different operating philosophy that undermined the integrity of the culture in which it was introduced. It delivered an innovation shock and sparked network effects long before that concept was conceptualized. Punk was a new industry model, one that changed and challenged those deeply embedded habits of thought which give a system its sense of direction and identity.

Or to frame it in terms of today's lexicon, Punk was a strategic transformation. Nothing was sacred. You could lose yourself in a reactionary had-it-up-to-here fury while also fully savoring the rupture, the novelty of the moment as a cathartic split from convention. Punk was completely different wattage.

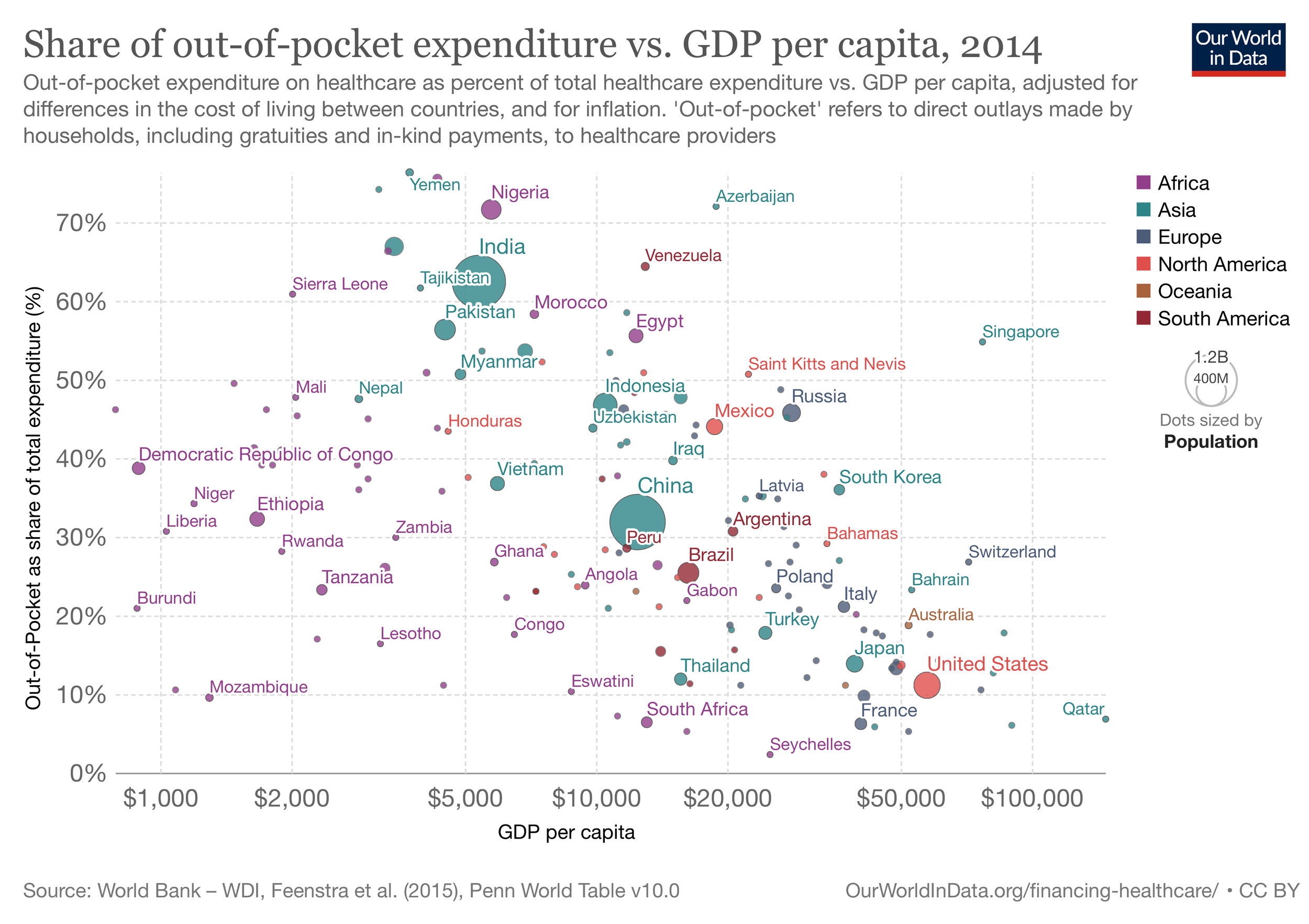

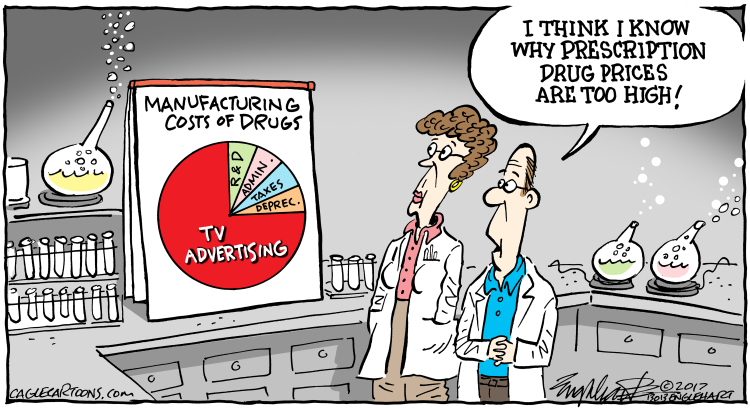

We are now in the 54th year of the official US healthcare "crisis."

For more than two generations, ballooning health care costs have been a source of concern, confusion, complexity and impending catastrophe when, on July 10, 1969, President Richard Nixon proclaimed, "We face a massive crisis in this area." Without prompt administrative and legislative action, he added at a special press briefing, "we will have a breakdown in our medical care system."

Failure takes time.

Healthcare is an unfixable economic system, at least in its current configuration of power and control. Perpetual "crisis" is sustained by structural stalemate and the 'organized irresponsibility' of a massive flywheel. Managed by expert knowledge of the past, trapped by technical debt and led with obsolete narratives and narrow framings, the "mother of all markets" spins around itself as an infinitely recursive problem. The writing is overwritten by the same assemblage of words, a 'sea of sameness' in which the content and communications is powerless to punch through, much less inspire or persuade.

We are at war with cliche.

And rather than aiming for new storylines, the lead actors perform similar roles with exaggerated gestures and ornamental waves to “patient centricity”, and the audience knows ahead of time at which points to boo and when to cheer.

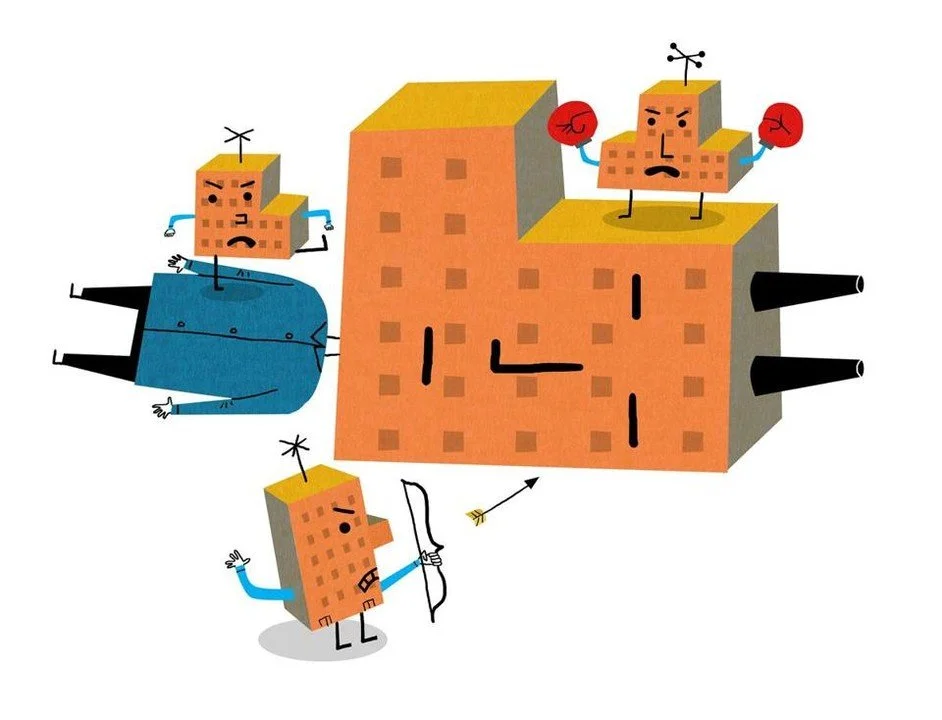

The bold imagination + big action skill for the next generation of health market leaders is the ability to creatively explore and conceptualize new territory, quickly assemble and sell the intellectual viewpoint, and then construct the health infrastructure -- the new industry ecosystem -- to own the space. In other words, tear it down and start over with new system vision. Chop the knot. Sweep the old concepts out of the saddle. Organize markets to interoperate within the context of new economic systems.

It's the ‘competitive mindset’ that needs a big rethink, in every industry + government market, which is all of them.

Where conventional strategy plays the player, strategy at a system level plays the board. Particularly if the objective is to “crack” a $4.3 trillion industrial complex, which, using one recent news-like example, Google is attempting “in its battle with Microsoft” to bring recent advances in artificial intelligence to healthcare (see: In Battle With Microsoft, Google Bets on Medical AI Program to Crack Healthcare Industry here).

Let’s say Google/Alphabet repositions itself as a keystone in a new industry ecosystem, part of a ‘design management team’ holding together a new system of “diabetes” markets — Google (the $300 billion technology services market) + Dexcom (the $17 billion continuous glucose monitoring market) + Eli Lilly and Company (the $100 billion GLP-1 drug market) + BASF (the $23 billion personalized nutrition market). What happens creatively is Google/Alphabet now invents new economic space for it to beat Microsoft acting and selling itself alone as a technical input to current operating models.

Where Microsoft competes on technical value, Google’s basis of competition is on ‘ecosystem value’.

Market Access Innovation

An economic system that is optimized to churn out strategies, markets and technical inputs to make the consumption of health services more efficient is impossible to “fix”. The gravitational pull is too strong. The jungle of complexity is too dense. The technical debt is too extreme. The legacy narratives too powerful.

Simpler to chop the Knot.

That’s the nut of things from economists Liran Einav of Stanford and Amy Finkelstein of MIT for how to “transform” the multi-dimensional dysfunctionality that is the $4 trillion apparatus of healthcare in the United States – and it’s detailed in their new book, We’ve Got You Covered: Rebooting American Health Care. They argue that our healthcare system was never deliberately designed around the production of affordable health, but rather pieced together to deal with issues as they become politically relevant.

“Few of us need convincing that the American [way of healthcare] needs reform. But many of the existing proposals focus on expanding one relatively successful piece of the system or building in piecemeal additions,” they explain. Nearly all of these proposals miss the bigger point.

Einav and Finkelstein believe it’s time to stop putting Band-Aids on a system they diagnose as “incoherent, uncoordinated, inefficient, and unplanned.” The result is a sprawling yet arbitrary and inadequate mess.

The ‘Production of Health’

A new test for market access innovation is how well commercial teams understand 'strategic competition' as an enduring condition, something to be managed, not a problem to be solved. And the skill to make that happen sits on core principles of constructive, collaborative, creative and results-oriented leadership. In other words, the real "battle" is about producing better outcomes, not consuming more inputs.

Roadmaps to ‘the next 100 billion’ in growth from the largest and most lucrative market on Earth starts by leapfrogging complexity and with new system vision. And if you buy into common sense, that it's not just one market that determines health “value” but an infinite flow of them, then a strategic advantage goes to leaders with the skills to harness a carnival of markets and manage them as a new economic system (“ecosystem”).

Winners have the better vision of serving (and sustaining) the ‘production of affordable health' over time.

Fragmentation is a design problem: there are islands of features everywhere from too many vendors wandering on the edges, pushing point solutions to small problems. The challenge is pulling it all together in a way that a whole system is born and becomes focused on generative value. The new data that flows from this new system, and then refined into specialized cognition, is the thing that generates new business value, supports population health and guarantees performance.

Data on purpose. You design for the analytics you want to capture.

Everything “digital” plays a supporting part in this story, not a lead. Technology is a means to dissolve boundaries, enable new positioning, remove friction and re-configure entire business systems, practically overnight. It's not about optimizing the past, but intentionally displacing the status quo.

“We wrote this book because, after studying U.S. health policies for almost two decades, Amy and I realized that we have something to say about the big picture,” says Einav. “And because we are outside of the political world, we think we have a fresh perspective and can maybe move the conversation in the right direction.”

It’s the kind of creative destruction the Sex Pistols would appreciate 🤘

/ jgs

John G. Singer is Executive Director of Blue Spoon Consulting, the global leader in strategy and innovation at a system level. Blue Spoon specializes in constructing new industry ecosystems. Disclaimer: Blue Spoon does not have a financial relationship with any brand mentioned in this article.